Guest post from Jessica Owens at Face ..

Did the #WaitroseReasons Twitter promotion snatch success from the jaws of disaster – or the other way around?

Three weeks on, marketers are still talking about it: it’s clearly made impact on one group at least! But to us, as social media researchers immersed in hundreds of comments every day about how people talk about brands, much of the analysis seems naïve, based on an overly superficial understanding of what people are doing when they talk on social media. A hint: they’re not really talking about your brand…

But before we explain why, a summary of the Waitrose kerfuffle:

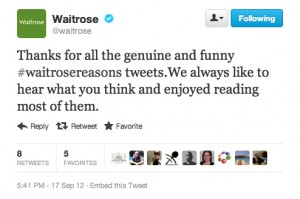

On 17th September, @Waitrose asked their customers to share their reasons for shopping at Waitrose, using the hashtag #WaitroseReasons. They got a lot of responses – probably not in quite the style they expected… Instead of an outpouring of brand love and affirmation, Twitter became a torrent of snark:

Oops. The runaway Twitter discussion produced a corresponding surge in digital industry & marketing press and blogs trying to make sense of the situation.

This followed a classic dialectic trajectory – first, the stern claims that “Waitrose was asking for trouble”, followed by enthusiastic rebuttals that all publicity is good publicity, and all ‘engagement’ is a sign of brand affection. But this hasn’t culminated in synthesis, but rather name-calling: specifically, Mark Ritson in Marketing Week arguing “Why marketers are socially stupid ”. A bold claim: let’s examine it.

Ritson begins by making a very important point: situating Waitrose’s social media tactics in the context of their overall brand strategy:

“The ultimate purpose of Waitrose’s social media strategy is not to start conversations or increase the number of followers the brand has on Twitter. The purpose of Waitrose’s social media strategy is to build its brand and increase sales. Waitrose has had a successful strategy to do just that, built around two approaches – first, getting existing shoppers to shop more frequently at Waitrose and second, attracting new shoppers into the stores.”

This is really important, and not often enough done. We entirely agree – volumes of mentions or retweets are not a meaningful end in themselves, and social media metrics shouldn’t blind researchers or brands to the real goals.

What we disagree with is his next claim:

“But this campaign inadvertently positions the supermarket as posh, snobby, overpriced and reserved exclusively for the upper classes. That’s terrible news for Waitrose, because it has spent the past four years positioning its brand away from these stereotypes and towards a more accessible, value-based position to drive market share gains.

[…] Existing shoppers at Waitrose, the middle-class segment it targets, will feel sensitive and perhaps a little less enthusiastic about entering the store now, and store traffic will decline. Potential converts to Waitrose will have had their stereotypes confirmed and be less likely to consider the switch in future. Perhaps neither of these impacts will be huge, but they will be negative and they were self-inflicted.”

What’s Ritson’s thesis – that people will take the “butler” and child-called-Orlando comments literally, and conclude that Waitrose is not a place for people who don’t have these things? This is suggesting someone’s “socially stupid” – but not the marketer: the Waitrose shopper. Twitter might allow only 140-characters, but we argue there was a lot of social nuance encoded in those tweets.

Defining features of British humour and culture: self-deprecation. Sarcasm, irony. We refuse to take ourselves seriously, and we’re somewhat keen on a bit of understatement. As a result, every international guide to British culture puzzles over the way we never seem to say what we mean. “Your report was… quite good”, says your boss with a wince. Rosie Huntingdon-Whitely “scrubs up alright”.

“Put the papaya down, Orlando!” has to be read through this lens – understanding its meaning through considering what is implied, what is inverted, and the shared tacit knowledge that’s referenced. This includes:

- Orlando is a slightly silly & pretentious name for a child – and giving children slightly silly & pretentious names is a middle-class social trend

- Recognising this shows familiarity with this class, and suggests the speaker is of this background or close to it – so it’s also a self-deprecating joke (which aren’t aggressive but rather inclusive – inviting recognition)

- Recognising buying exotic fruit like papayas as another signifier of middle-class identity…

- …and moreover the behaviour of talking loudly about specialist foods in order to demonstrate and assert middle-classness

- Using irony and sarcasm to show that you’re not “taken in” by the brand’s marketing – (you believe) you’re subverting it

- And by the way, the kind of person who does all these things would typically shop in Waitrose.

In fact, this is what almost all the #WaitroseReasons tweets were doing: making observations that demonstrate the author’s familiarity with and membership of a specific segment of the more comfortably-off middle class.

It went big on Twitter, because it was a way for people to talk about their favourite topic: themselves. The discussion around the hashtag wasn’t really about Waitrose as a retailer so much as a way for people to start talking about that great British obsession, social class, and where we fit into the hierarchy. It was a discussion about belonging: people were collectively & collaboratively playing with the boundaries of belonging to the middle class. Waitrose was just a signifier – a particularly rich and meaningful one, a national treasure whose meanings are owned by its customers (not just its marketers).

In fact, it mightn’t be something marketers want to hear, but people don’t really want to have relationships with brands as such. If you think about it, it’s pretty weird – a passionate love affair with the nexus of meanings encapsulated in your shampoo bottle? No: as Mark Earlsargues in ‘Herd’ (and we discuss in Augmented Research ), “We talk of the relationships consumers have with our brands as if they were primary, but consumers’ most valuable relationships are not with brands but with other consumers.”

#WaitroseReasons was a chance for people to demonstrate their social tribe allegiance and how witty & clever they could be – two very desirable social markers, hence the massive participation. It’s basically #MiddleClassProblems with a brand attached. Was this Waitrose’s strategy? It’s not clear. It certainly was Alan Sugar’s, though, who invited people to share #TheWayISeeIt for the launch of his book – gaining 390,000 tweets, celebrity involvement and major press coverage from giving people a chance to share who they were.

But what about Mark Ritson’s second point: that #WaitroseReasons was exclusionary, that it was sending too many people a message of “not for me”?

There’s a grain of truth in this. What Waitrose did was bold – it wasn’t an ‘everyman’ strategy but rather spurred discussion about group norms. As such, this is necessarily a “boundary policing” activity, one that defines who’s the “us” who share these norms, and by logical extension who’s the “them” who doesn’t. And yes, for some people kids called Orlando and fruit like papayas are pretty far from their lives.

But brands have to do this – they have to define their audiences and target markets, rather than hoping to be all things to all people. Waitrose is a middle-class brand, its locations, pricing, product range and marketing all make this clear. Its value strategy is merely about trying to appeal to a more budget-conscious middle class shopper who might have moved away – they were never staking their claim to Asda’s demographic. It’s about consolidating loyalty.

By participating in a discussion about social norms, then, Waitrose strengthens its identification with this middle-class group. By being able to “take a joke” and “keep their chin up” during a hazing ritual, Waitrose comes out of a social media pasting showing they can demonstrate English middle class values too.

And connecting social activity back to brand strategy, then hopefully we’ve made it clear that this isn’t just a win on awareness. No: it’s also a complex but powerful statement of identification – and thereby brand loyalty. And brand loyalty gets feet through the door and keeps the tills ringing.